When countries put forward their climate proposals for the Paris Agreement, they were asked also to explain why these are ambitious. Countries found many ways to make their case: For example, the USA stated that its new proposal requires faster reduction than their earlier one. The EU declared that it wants to decrease emissions until 2030 by at least 40% since 1990, more than most other countries. China wants to peak its emissions before 2030 at a lower level (per capita) than for example the USA. If countries use different ways to describe their ambition, how do we know if one is more ambitious than the other? Only a comprehensive approach that covers all perspectives can be used to assess ambition of national climate policy – argues the new scientific article “Assessing the ambition of post-2020 climate targets: a comprehensive framework” by NewClimate Institute and and the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency PBL.

The adoption and entry into force of the Paris Agreement is a big step forward in international climate policy. Nearly 190 countries submitted their proposals on how, and by how much, they are willing to reduce their GHG emissions after 2020; these are the so-called ‘intended nationally determined contributions’ (INDCs). Upon ratification of or accession to the Paris Agreement, a country’s ‘intended nationally determined contribution, INDC’ turns into a ‘nationally determined contribution, NDC’.

Unfortunately, the total ambition level of all national contributions is not yet sufficient to achieve the global goals of the Paris Agreement, i.e. to limit the increase of global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5°C.

Consequently, all countries are asked to revise their contributions and to increase the level of ambition over time. To guide this process, the NDCs of countries will have to be assessed on their relative ambition level. In fact, raising ambition is more likely if all countries agree that they are all at around the same ambition level that is appropriate for their national circumstances.

But how to assess the ambition level of climate policy?

If countries use different ways to describe their ambition, how do we know if one is more ambitious than the other? Countries found many ways to make their case:

- USA promised to reduce their emissions in 2025 by 26% to 28% below 2005 level and state that its new proposal requires faster reduction than their earlier one.

- The EU promised to decrease emissions until 2030 by at least 40% since 1990, arguing that this is more than most other countries.

- China wants to peak its emissions before 2030. They claim that this is a peak at a lower level (per capita) than others before them.

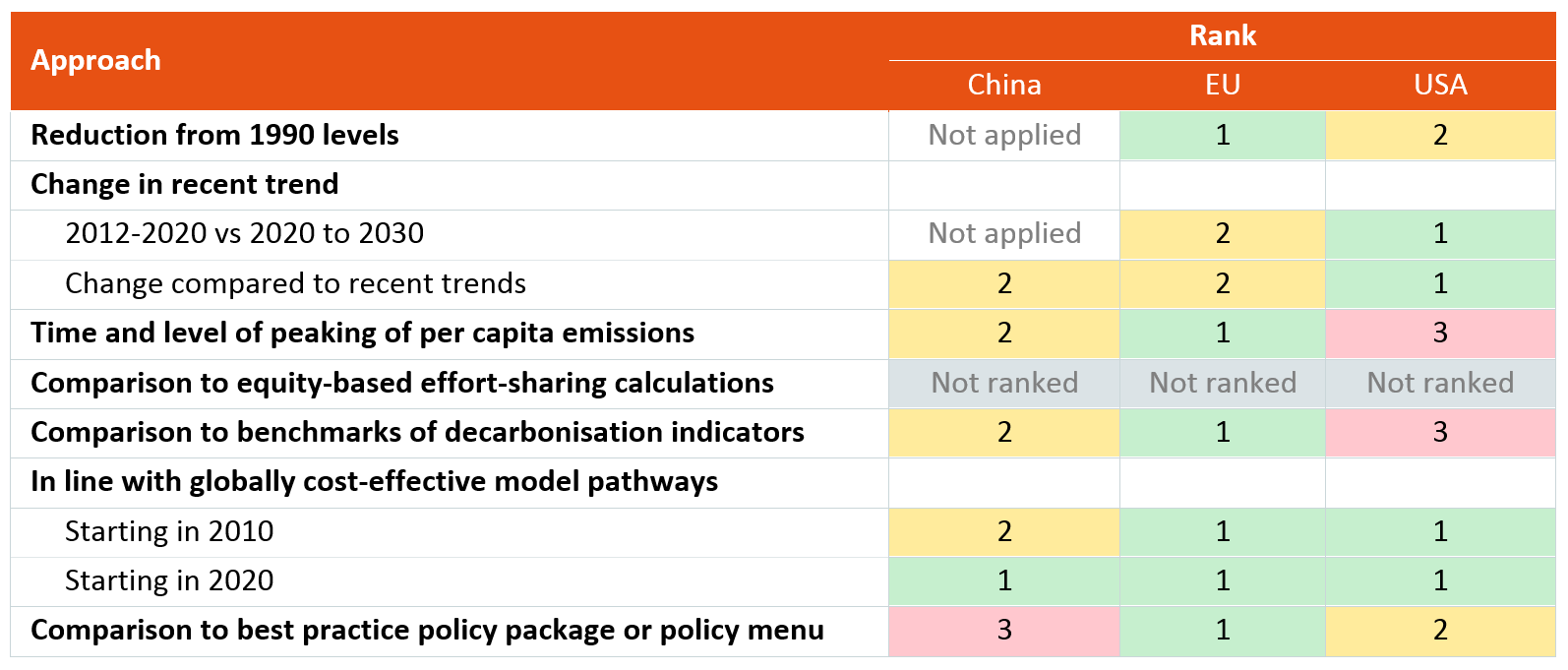

In this new paper, we applied all different principles and arguments to assess ambition that we were aware of to the different country proposals, illustratively here for China, EU and the USA. If a country scores well on all of them, it can definitely be classified as ambitious. If it doesn’t score well on any of them it is definitely not ambitious. And if the different approaches give mixed signals, this highlights where improvements may be possible.

The following principles used by countries to assess ambition are considered in the paper:

- A country’s reduction of emissions since 1990: the standard perspective for developed countries since 1992, also used in the Kyoto Protocol – a preferred metric by the EU.

- Change in recent trend in emissions: a country would do more than before – the main argument in the proposal by the USA.

- Time and level of peaking emissions per capita: countries go through different levels of development with first rising, then peaking and then declining emissions – the metric chosen by China.

- Comparison to equity-based effort-sharing calculations: There is a long history of scientific studies that calculate “fair” emission targets of countries ‘effort-sharing’ principles. The principles include responsibility (e.g. those who emitted more in the past now have to reduce more) or capability (e.g. those with higher per capita income levels should do more), equality (i.e. equal emission rights per capita), cost-effectiveness (total abatement cost per GDP), as well as combinations.

- Comparison to benchmarks of decarbonization indicators: A number of indicators can be used to describe countries’ circumstances and developments, e.g. on the national level emissions per capita, energy use per capita or the energy mix. On the sectoral level it could be emissions per kilometre travelled or per tonne of cement or steel produced. Indicators can measure activity (e.g. vehicle kilometres travelled) or intensity (emissions per vehicle kilometre) (see also the data portal of the Climate Action Tracker).

- In line with globally cost-effective model pathways: Modelling exercises can identify required reductions by countries on the principle of minimising the aggregated global costs of emission reductions. As a result, reductions are required in those sectors and countries where they are least cost from a global perspective.

- Comparison to best practice policy package or policy menu: One can compare the extent to which a country implemented supporting policies, addresses barriers, or has counterproductive policies in place. A contribution can be regarded as ambitious if it includes many policies that are considered good practice, while it would be less ambitious if the country were not to implement the policies that most of its peers have already successfully implemented (see also climate policy database).

What are the results?

As expected, example countries used in the analysis score very differently across the approaches. However, the collective results show certain tendencies. For example, the EU scores highest among the three on many approaches (in many cases together with China and/ or the US). Only when using the principle of “changes in recent trends” (the metric that the USA chose to explain its ambition) is the US clearly ahead of the EU.

The comparison of China and the US is, in essence, determined by how far the different development levels should be taken into account: China is consistently ahead of the US when considering decarbonization indicators and level and timing of peaking emissions. Owing to a lower development level, its emission intensity and activity levels are lower than in the US. The US, on the other hand, has a more comprehensive policy package and proposes more change from the current policy scenarios.

The overview evaluation highlights the shortcomings of each proposal and therefore provides insights into where improvements could take place. Although the EU scores well on many aspects, our framework shows that the current NDC means only limited progression from current trends. For the US, even with a step change in policy, our comparison of approaches shows that activity and energy intensity levels are still much higher than in other countries. Regarding China, although its activity and energy intensity indicators are still low and it is undertaking significant policy efforts in some areas, the analysis reveals that many policy areas remain unaddressed.

So what have we learned?

Firstly, a comprehensive assessment of ambition of climate proposals can only be undertaken using a large variety of evaluation approaches. Each single approach has its pros and cons, starts from a very particular perspective, and no single approach is truly comprehensive. The different nature of the evaluation approaches leads to different outcomes; only if all of them are applied, does it become evident if a country is broadly ambitious, or only under very selective perspectives. Such a comprehensive approach could therefore be usefully applied when considering ways to raise ambition. The Paris Agreement suggests that this should happen at the “facilitative dialogue” in 2018, and the “global stocktake” that is to take place every five years starting from 2023.

Secondly, we put forward a comprehensive framework of evaluation approaches that covers, to our knowledge, the broadest possible range of approaches. The framework evaluates countries using all eight approaches shown here, rank countries relative to each other where possible, and present the results alongside each other (without aggregating into one overall rating).

Finally, we find that the illustrative application of this framework provides useful insights even if the ambition level of China, the EU, and the US varies, depending on the perspective taken. The EU ranks consistently first or second across many of the approaches. Only when considering “changes in recent trends” is the US clearly ahead of the EU. The comparison of China and the US is, in essence, determined by how far the different development levels should be taken into account.