In November 2023, the German government introduced its first-ever climate strategy for federal export credit guarantees, so-called Hermes covers. The strategy aimed to align export credit support with Germany’s climate objectives by offering preferential conditions for climate-friendly projects across several sector guidelines, including energy, chemicals, metals, civil aviation and shipping and passenger and commercial vehicles.

The strategy is now heading into its first revision cycle. The government will review the sector guidelines for the first time in 2026 (originally planned for 2025) and every three years thereafter. A public consultation is expected in early 2026 following the release of the revised guidelines.

A central issue in the upcoming revision will be the eligibility criteria for fossil gas turbines and fossil gas-fired power plants. Under the current guidelines, coal-fired power plants have been excluded from Hermes cover since 2020. However, fossil gas projects can still be eligible under certain conditions if they demonstrate readiness for hydrogen use or qualify as a ‘coal-to-gas shift’ under specific criteria.

How these criteria are defined matters. They will determine whether the revised climate strategy helps avoid new fossil lock-in or allow public-backed support for fossil gas infrastructure that is incompatible with the Paris Agreement.

Ahead of the public consultation, in which NewClimate Institute will participate, this blog post revisits what the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit implies for fossil gas infrastructure and the role of federal export credit guarantees. More specifically, it explores what it would take for eligibility criteria to reflect 1.5°C compatibility in practice.

In short, we argue that independent assessments of national or corporate climate targets alone are not sufficient as standalone eligibility criteria for Hermes cover. Instead, the revised criteria should require fossil gas project developers to demonstrate that any additional fossil gas capacity is compatible with a 1.5°C-aligned decarbonisation pathway for the power sector in the relevant country context.

This approach would also help Germany, as a signatory to the COP26 Statement on international public support for the clean energy transition, more credibly fulfil its commitment to limit public support for unabated fossil fuels to clearly defined 1.5°C-compatible circumstances.

The Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit and its role for export guarantees

The German government’s coalition agreement of 2025 reaffirmed its commitment to implement the Paris Agreement. While not directly referring to the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit, the International Court of Justice’s 2025 advisory opinion on the Obligations of States in Respect of Climate Change finds that ‘1.5°C has become the scientifically based consensus target under the Paris Agreement’. This was reaffirmed by the Mutirão Decision at the Conference of Parties (COP) 30 in November 2025, which further emphasised the need to limit any overshoot above 1.5°C both in magnitude and duration. Taken together, this strengthens the case for treating 1.5°C temperature limit as the relevant obligation and legal benchmark for governments under the Paris Agreement.

The 1.5°C temperature limit therefore remains a key determining factor for any decisions on new fossil gas infrastructure, including the German government’s Hermes covers for fossil gas turbines or fossil gas-fired power plants.

It is clear that the role of fossil gas under the remaining global CO₂ budget consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit is very limited and fossil gas use must be rapidly phased down. Fossil gas has substantial lifecycle emissions, and safeguarding 1.5°C requires a rapid decline in both its production and combustion. The challenge lies in operationalising this in practice – particularly where claims are made that fossil gas could play a ‘transitional’ role. As argued in our recent blog post, there is no room and no necessity for new fossil gas production, nor for new export infrastructure that drives further exploration, development or long-term fossil lock-in.

At the same time, in some country contexts, fossil gas may still play a strictly limited, transitional role during the phase-out on the path to net zero – for example to temporarily support system stability or address acute energy security concerns. Even in such cases, 1.5°C compatibility can only be claimed where these circumstances are narrowly defined, robustly evidenced and explicitly time bound and where zero-carbon alternatives are not accessible.

As export credit rules for the fossil energy sector are revised, the key question is how the German government can assess whether – and under what conditions – federal export credit guarantees can ensure 1.5°C-compatibility.

Independent climate target assessments: not sufficient as standalone criteria for export guarantees

The existing 2023 fossil energy sector guidelines allow export guarantees for fossil gas turbines or fossil gas-fired power plants in two scenarios: where a turbine or plant can directly be operated with hydrogen or where it represents a ‘coal to gas shift’. The latter hinges on three criteria: (a) the German contribution is demonstrably at least 50% hydrogen-ready, (b) the German supplier provides evidence of 1.5°C compatibility of its portfolio along all value chain emissions – for example through a Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) validation; and (c) the additional capacity is line with the country’s documented 1.5°C-compatible decarbonisation pathway.

In revising the eligibility criteria, independent assessments of national and corporate climate targets, such as SBTi validations, are often considered. However, it remains unclear whether, and how, such assessments could credibly serve as standalone criteria in the revised sector guidelines. Three options could be considered, which we discuss below:

Option 1 | Use independent assessments of national climate targets

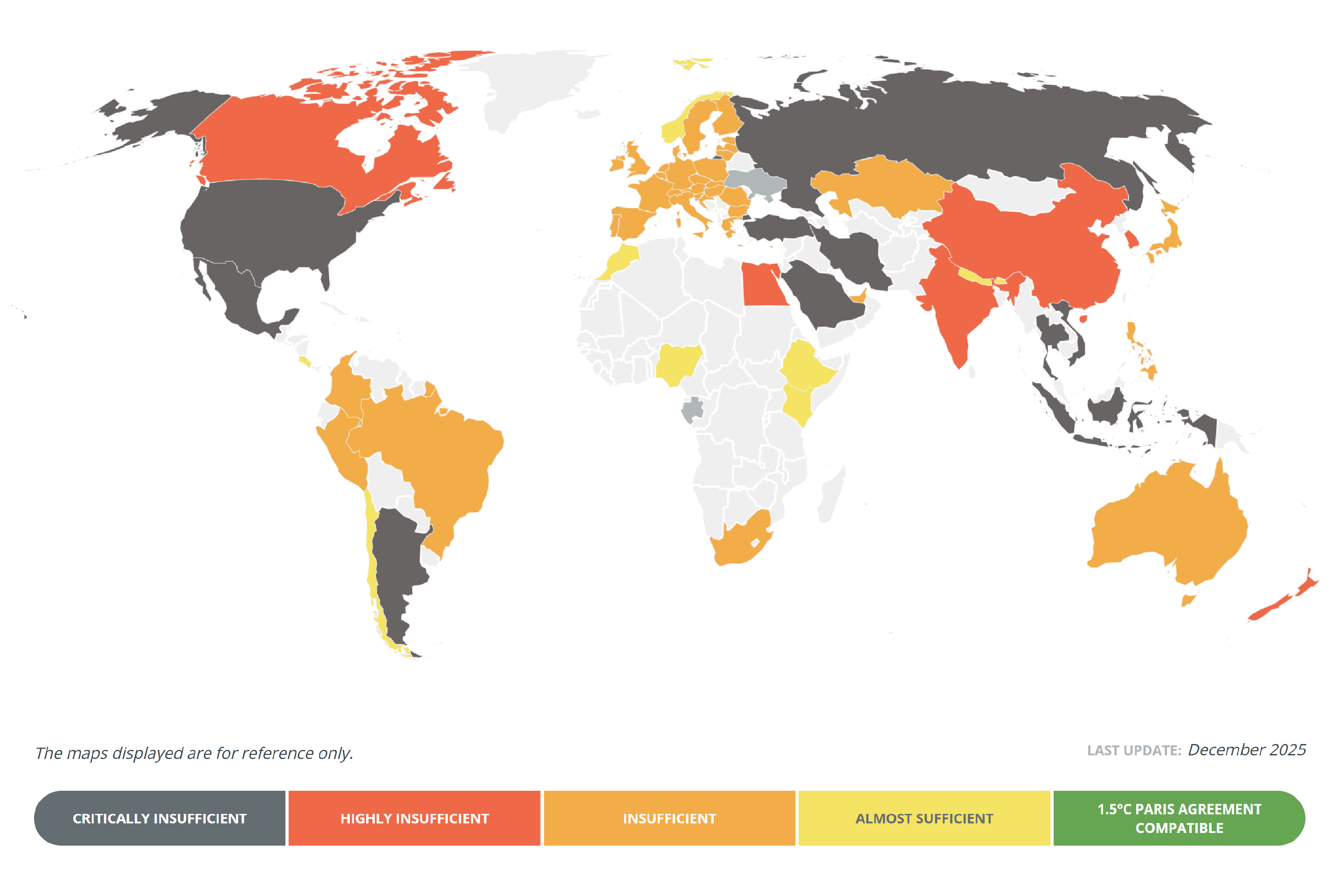

For the eligibility criteria, independent assessments of national climate targets and strategies could be considered – for example, the Climate Action Tracker (CAT), which assesses the adequacy of national-level climate targets, policies and action and climate finance for 40 countries.

Under this option, the importing country would need a "1.5°C Paris Agreement-compatible" rating for the German government to provide a Hermes cover. None of the 40 countries assessed by the CAT is currently rated as 1.5°C compatible (see Figure 1). This includes recent export destinations of German manufacturers like the United Kingdom, rated as "insufficient", and China, rated as "highly insufficient". Other recent export destinations like Uzbekistan, Iraq or Hongkong are not covered by the CAT.

Figure 1: Climate Action Tracker assessments of 40 countries as of December 2025.

The CAT headline assessments, however, do not indicate whether additional fossil gas generation capacity is compatible with 1.5°C-aligned decarbonisation pathways. The headline ratings aggregate many elements of climate policy (e.g. 2030 targets, policies and actions or climate finance), of which the building of additional gas-fired power plant capacity is only one small aspect. Other aggregated country assessments, such as the Climate Change Performance Index for 60 countries, have a similar limitation.

For these reasons, we do not recommend using independent aggregated ratings of national climate targets and strategies as standalone criteria for Hermes cover, as they are not specific enough for the question at hand.

Option 2 | Use independent assessments or validations of corporate climate targets

A second option would be the use of independent assessments or validations of corporate climate targets and strategies, similar to how the current sector guidelines refer to the validations by the SBTi.

As of December 2025, the SBTi has validated corporate climate targets for around 10,000 companies. Other initiatives also exist, such as the Transition Pathway Initiative (TPI), which assesses the carbon performance of corporate climate targets of around 550 companies. Such assessments could be required either for exporting German suppliers of fossil gas turbines or plants or for importing foreign companies such as energy utilities.

As for exporting German suppliers, we recommend against using such assessments as eligibility criteria, even where they consider downstream scope 3 value chain emissions, such as use-phase emissions from operating a fossil gas turbine.

The assessments by SBTi or TPI do not consider the specific power sector conditions in the countries to which German suppliers export. Moreover, none of the major German suppliers, such as Siemens Energy1, MAN Energy Solutions or Jebsen & Jessen Industrial Solutions GmbH, currently have 1.5°C validations by SBTi or TPI that cover downstream scope 3 emissions.

For importing foreign companies such as energy utilities, we also consider current assessments not suitable as standalone eligibility criteria.

Current methodologies such as the SBTi’s Corporate Net Zero Standard v1.3, the SBTi’s forthcoming Power Sector Net-Zero Standard or the TPI’s Methodology for Electricity Utilities v5.0 are based on global or regional 1.5°C-compatible pathways. However, they do not systematically reflect country-specific information on power sector decarbonisation. Assessing a single importing company in isolation would be therefore insufficient.

For example, an importing company with 1.5°C-validated targets could only have renewable capacity in its generation portfolio and yet still decides to build a fossil gas-fired power plant, even where many other gas-fired power plants already exist in the country, owned by other companies. While TPI’s methodology (EU, North America, OECD, non-OECD) and the forthcoming SBTi power sector methodology (OECD and non-OECD) considers some regional decarbonisation assumptions and regional phase-out dates for fossil-based electricity generation, these do not necessarily reflect country-specific 1.5°C power sector pathways.

Option 3 | Use a combination of both approaches

A third option would be to combine independent assessments of national climate targets with assessments of corporate climate targets.

This option would cover specific information on both the importing country and the importing company. However, it would still face the same limitation: neither country-level nor company-level assessments explicitly indicate whether additional fossil gas generation capacity is compatible with 1.5°C-aligned decarbonisation pathways.

While such a combined approach would likely rule out further Hermes covers for fossil gas turbines and fossil gas-powered plants, it would so for the wrong reason – by excluding projects based on broad ratings rather than through a context-specific assessment of whether additional gas capacity is consistent with the importing country’s power sector pathway.

The way forward for Paris-aligned Hermes guarantees

There is no simple, universal criterion that can be applied to greenlight Hermes covers for fossil gas turbines or gas-powered plants, given the country-specific context. As explained above, we therefore recommend against using independent assessments of national or corporate climate targets as standalone criteria in the revised fossil energy sector guidelines.

So, what should credible eligibility criteria look like?

We argue that the German government should shift the burden of proof for demonstrating 1.5°C compatibility to the respective project developer or buyer. This way, project developers or buyers would need to prove how a newly built fossil gas-powered plant fits into a coherent and time-bound energy transition pathway for the importing country in line with the 1.5°C temperature limit. To enable this, the German government should further develop criteria to evaluate such a country-specific proof by project developer or buyer.

At its core, such a country-specific proof would need to justify why additional fossil gas generation capacity is the only available option in the specific country context to achieve a 1.5°C-aligned decarbonisation pathway. For example, this would require proof that peak generation capacity running on fossil gas is needed because (a) the country has already achieved a very high share of variable renewable electricity, such as wind and solar, and (b) no other low-cost storage and flexibility alternatives, such as large-scale battery storage, are available. In addition, it would require proof that the additional fossil gas capacity does not jeopardise (c) full decarbonisation of the electricity system well before mid-century, latest by 2035 for developed countries and latest by 2045 for other emerging developing countries, in line with the IEA Net Zero Roadmap. The German government should carefully develop nuanced criteria, informed by further research.

Shifting the burden of proof can more credibly safeguard that any newly built fossil gas-powered plant supported by the German government through Hermes covers, if any at all, contributes to ambitious energy transition aligned with the latest scientific findings.

Once the new fossil energy sector guidelines are released, NewClimate Institute will review them and participate in the forthcoming public consultation.

The authors thank Niklas Höhne, Thomas Day and Laeticia Ock for their content and editorial review.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of NewClimate Institute or the funder.