The Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity initiative (VCMI) has released its integrity guidelines for corporate use of carbon credits. In some regards, the concept of VCMI’s Silver, Gold and Platinum claims set out a transparent and constructive approach. But the Scope 3 Flexibility Claim will be the most relevant part of the claims package for the next decade. This flexibility claim – launched as a “beta” version – offers a free pass to corporates, providing enough flexibility to render many of their 2030 scope 3 targets as meaningless. The most ambitious 2030 pledges are reduced to marginal emission reductions that would be highly unlikely to require any action beyond business-as-usual developments. Many other companies with SBTi-validated 2030 targets no longer need to reduce their scope 3 emissions up to 2030 at all, but may rather significantly increase their emissions.

Corporate climate pledges including scope 3 emissions for 2030 fall well short of the economy-wide emission reductions required to stay below the 1.5°C temperature limit

The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report finds the need to cut global economy-wide GHG and CO2 emissions by 43% and 48% between 2019 and 2030 respectively, to be in line with the goal to limit the global temperature increase to 1.5°C (IPCC, 2022).

Against this scientific backdrop, companies with emission reduction targets validated by the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) currently fall well short of these required ambition levels across their entire value chain emissions. For the 22 companies assessed in the 2023 Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor (CCRM) with targets for 2030 – most of which are validated as 1.5°C by SBTi – we find that these targets translate to a median absolute emission reduction commitment of just 15% of the full value chain emissions between 2019 and 2030. This may increase to 21% under the most optimistic scenario that emission intensity targets translate to equivalent absolute emission reductions.

Two reasons for the discrepancy include the little-known fact that SBTi’s temperature alignment ratings for 2030 do not cover scope 3 targets with a few exceptions, and the fact that accounting issues – such as scope exclusions, strategic base year selection, and carbon dioxide removals – mean that the 2030 targets that companies propose are often not what they say on the tin. Scope 3 emissions – upstream and downstream emissions from the value chain – account for the vast majority of most companies’ GHG emission footprint.

The uncertainties and potential shortcomings of the VCMI’s scope 3 flexibility claim

The Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity initiative was established in 2021, with the objective to “enable high-integrity voluntary carbon markets”. The VCMI Claims Code of Practice – launched in November 2023 ahead of COP28 – is intended to be a demand-side rulebook on how companies can make voluntary use of carbon credits as part of credible, science-aligned net-zero decarbonisation pathways (VCMI, 2023a)

VCMI’s beta scope 3 flexibility claim would allow companies to purchase carbon credits for up to 50% of their annual scope 3 emissions to “bridge the gap” to the scope 3 target trajectory that they are not on track to meet (VCMI, 2023b). Whether or not this is an offsetting claim depends on one’s interpretation of terminology, but it certainly leaves open more than enough room for companies to use carbon credits as an alternative, rather than a complement, to cutting their own emissions.

What would this 50% flexibility claim mean in practice for companies’ 2030 scope 3 targets?

It is important to understand that the VCMI’s beta claim offers a 50% flexibility threshold compared to a company’s actual emissions in any given year, rather than 50% of the emission reductions necessary towards achieving the company’s target. In other words, companies can still be eligible to use carbon credits for the Scope 3 Flexibility Claim if their emissions are double the levels that would be implied by the target trajectory in any given year. In most cases, companies could significantly increase their emissions up to 2030, and still remain eligible for the claim.

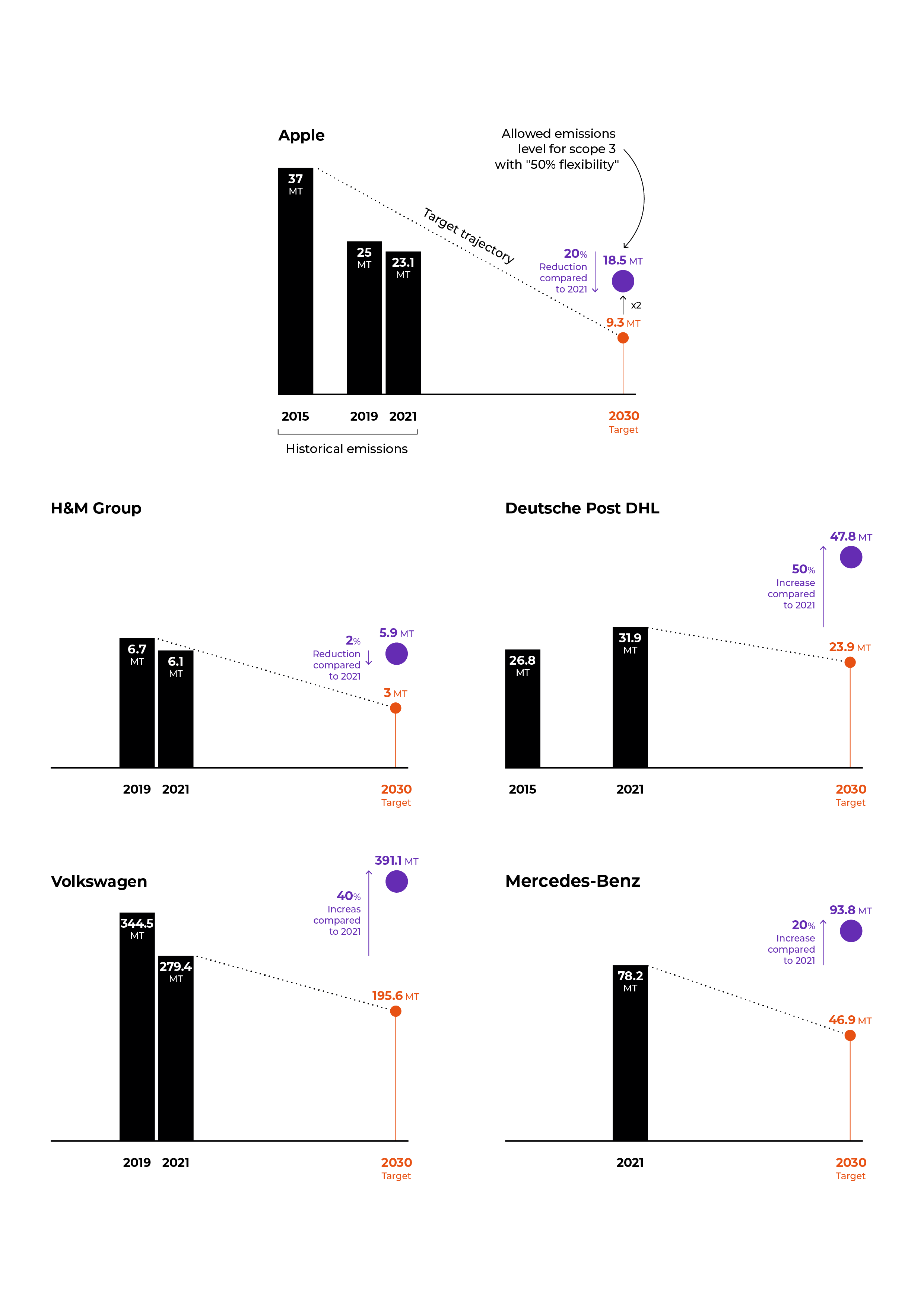

To illustrate the implications of the Scope 3 Flexibility Claim, we have tested it for a sample of five companies that have SBTi-validated 2030 targets and which were included in the 2023 Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor. These companies include those with ambitious emission reduction targets for 2030 as well as those whose reduction targets we consider having poor integrity. The following examples show how little these companies would need to achieve in terms of emission reductions to be eligible for using the Scope 3 Flexibility Claim to “bridge the gap” to their SBTi verified targets for 2030[1].

The most ambitious 2030 pledges are reduced to marginal emission reductions that would be highly unlikely to require any action beyond business-as-usual developments:

- Apple and H&M Group – the companies with the deepest scope 3 emission reduction targets for 2030, among the 24 companies covered in the 2023 CCRM – would need only to reduce their emissions by -20% and -2% between 2021 and 2030, respectively. Most of Apple’s scope 3 emissions derive from electricity consumed in the supply chain, an emissions source for which the emissions intensity is forecast to decrease by 34% between 2022 and 2030 under the IEA’s stated policies scenario, or 45% under the announced pledges scenario (IEA, 2023).

Other companies need no longer to reduce their scope 3 emissions up to 2030 at all, but may rather significantly increase their emissions:

- Mercedes Benz could increase the emissions covered by its scope 3 target by +20% between 2021 and 2030.

- Volkswagen Group could increase the emissions covered by its scope 3 target by +40% between 2021 and 2030.

- Deutsche Post DHL could increase the scope 3 emissions covered by its target by +50% between 2021 and 2030.

Under the current beta proposal, the role for carbon credits to “bridge the gap” should phase out by latest 2035, 12 years from now. This phase-out is identified as a “guardrail” for the Scope 3 Flexibility Claim. We do not consider this phase-out date to send a very meaningful signal, or to be an effective guardrail. We believe that companies will only plan with the voluntary carbon markets rules that they see for the next 5–10 years. Much will happen in international climate policy over the next 12 years; companies know it is almost inconceivable that the rulebook for the use of carbon credits will remain unchanged during this time. Thus the 2035 expiration is potentially meaningless, while companies have flexibility to continue business as usual in the short- to medium-term.

Recommendations for real integrity

“Integrity” is the buzzword of the hour for the voluntary carbon market initiatives and alliances being launched around COP28. But integrity in the current context and urgency of the climate crisis must be rooted in a transparent and honest discussion on what companies can achieve and what limitations they understandably face. We need mechanisms to increase the flow of voluntary climate finance without compromising that transparency.

- We need a clearer and stronger focus on scope 3 targets up to 2030, recognising that the existing level of ambition for corporate action up to 2030 is critically insufficient to be aligned with 1.5 °C compatible trajectories, even before any flexibility is introduced.

- Given that the Scope 3 Flexibility Claim centrally builds upon the SBTi’s methods to set and validate scope 3 reduction targets, SBTi should be clearer about the fact that its temperature ratings for companies’ 2030 targets generally do not apply to scope 3 targets, with a few exceptions. SBTi’s validations of 2030 targets do not mean that a company’s scope 3 targets are aligned with a 1.5°C trajectory, and in fact we find that these targets are far from aligned. We understand that this is a very common misconception.

- We need full transparency and constructive dialogue – rather than creative accounting tools and ambiguous claims – when companies (understandably) fall short of the hugely challenging level of necessary ambition.

- We need to incentivise voluntary climate finance from companies – for example, as currently proposed by various groups under the terms climate contributions or beyond value chain mitigation (BVCM) – without the insinuation of emissions being “neutralised”, or “bridging the gap”.

- If flexibility claims are politically unavoidable, the degree and timeframe of flexibility needs to be far tighter than those proposed in VCMI’s Scope 3 Flexibility Claim. Companies that are not taking any action on their scope 3 emissions at all should not simply be let off the hook.

Figure 1: Illustrative indication of the implications of the Scope 3 Flexibility Claim for a sample of 5 companies with SBTi validated targets.

Assumptions and calculation steps for the five companies’ scope 3 targets for 2030

The assumptions set out below are intended to be a transparent explanation of our indicative calculations for the implications of the Scope 3 Flexibility Claim for the five companies. We do not assert that these assumptions are necessarily entirely accurate in every case, but we are confident that these assumptions serve the purpose of providing a reliable indication of the order of magnitude, for illustrative purposes.

The five specific companies are only used as examples; we are not aware and do not intend to imply that these companies have indicated an intention to make use of the Scope 3 Flexibility Claim. Rather we just present an indication of what the VCMI claim would in theory allow these companies to do.

To calculate with what emissions level these companies would still be eligible to use the Scope 3 Flexibility Claim, we doubled their 2030 reduction targets. Under the Scope 3 Flexibility Claim, companies are eligible to purchase carbon credits to cover the “emissions gap” between their actual emissions in a given year and their targeted emissions level for that same year, as long as the number of carbon credits does not exceed 50% of the actual emissions. In other words, the emissions gap may be equal to the targeted emissions level. For instance, if a company commits to an emissions level of 40 Mt in 2030 and their actual emissions are 80 Mt in that year, the gap is 50% (80-40) and the actual emissions level double the size of the committed emissions level.

|

Apple |

|

|

Deutsche Post DHL |

|

|

H&M Group |

|

|

Mercedes-Benz |

|

|

Volkswagen |

|

References

IEA (2023) World Energy Outlook 2023. Available at: https://www.iea.org/topics/world-energy-outlook

IPCC (2022) ‘Summary for Policymakers’, in Pörtner, H.-O. et al. (eds) Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–33. doi:10.1017/9781009157926.002

VCMI (2023a) Claims Code of Practice: Building integrity in voluntary carbon markets. Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative

VCMI (2023b) Scope 3 Flexibility Claim - Beta version. Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI)