In 2023, the European Union is planning to introduce a major reform to its flagship emissions trading system, the EU ETS. The scheme to date has focused on cutting carbon emissions from economic activities – such as electricity generation or carbon intensive industry – carried out within the bloc’s borders. The new Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, or CBAM, extends the reach of the EU ETS to cover imports of certain products entering the European Economic Area. The CBAM replaces free allocation as the primary tool to protect trade-exposed sectors against carbon leakage. According to the provisional agreement reached by the Council and the European Parliament, the initial 3-year pilot phase of CBAM requires EU importers to report the greenhouse gases released during production (direct and indirect) of aluminium, cement, iron and steel, fertilizer, hydrogen, as well as electricity produced outside of the EU. The provisional agreement was preceded by long discussions on the scope and coverage of the mechanism. The goal is to extend the coverage of the mechanism to also include further commodities subject to carbon leakage, such as organic chemicals and polymers (plastics), as well as eventually all goods covered by the EU ETS. Once the CBAM enters into force in 2027, importers will need to acquire and surrender certificates corresponding to the greenhouse gases associated with imports from outside of the EU.

The CBAM was introduced to promote a level playing field in terms of the regulatory burden of climate policies between producers of similar products within the EU and outside of it. In many cases its introduction will reduce the competitiveness of carbon intensive products manufactured outside of the region. Many of the immediate considerations of the CBAM’s potential impact centre around countries who are key exporters of the affected products to the EU and therefore immediately and directly implicated.

In this blog, we look at the exposure of major Southeast Asian economies to CBAM in its likely future form (coverage including plastics as per proposal of EU Parliament) and apply an economic model (CLIMTRADE) to appraise several broader considerations that may arise from distortions to global trade flows.

Does CBAM pose a risk to countries exporting to the EU?

Producers that are either currently exporting to the EU, or intend to in the future, now have an extra incentive to consider the climate footprint of their activities. And the policy has the potential to impact trade flows beyond just those channelled into the EU. For example, if EU demand for imported steel falls as a result of CBAM, this can alter the balance of supply and demand on the global market and potentially lower steel prices exported into other, non-EU countries. Non-EU exporters of steel, aluminium or other products covered by CBAM will want to understand what risks they face to the value of their goods – either through changes to the volume of demand, or prices, or both.

CBAM related economic risks are difficult to measure. The extend to which a country is likely affected by CBAM depends, besides the EU ETS price and the stringency of CBAM, primarily on exporting countries’ exposure, i.e. the volume of affected exports to the EU. Exposure alone, however, does not say much about possible economic risks. A more relevant risk measure is vulnerability. Vulnerability measures economic dependency, export diversification, and export concentration besides exposure and thereby sheds light on those exporting countries that will potentially carry the largest burden of the mechanism. For example, a non-EU country would be most vulnerable if it was to predominantly produce and export CBAM-relevant commodities (lack of diversification) for the EU market (high concentration), and specifically if the country’s GDP strongly depends on these exports.

Southeast Asia is not highly vulnerable, but impacts are still sizeable

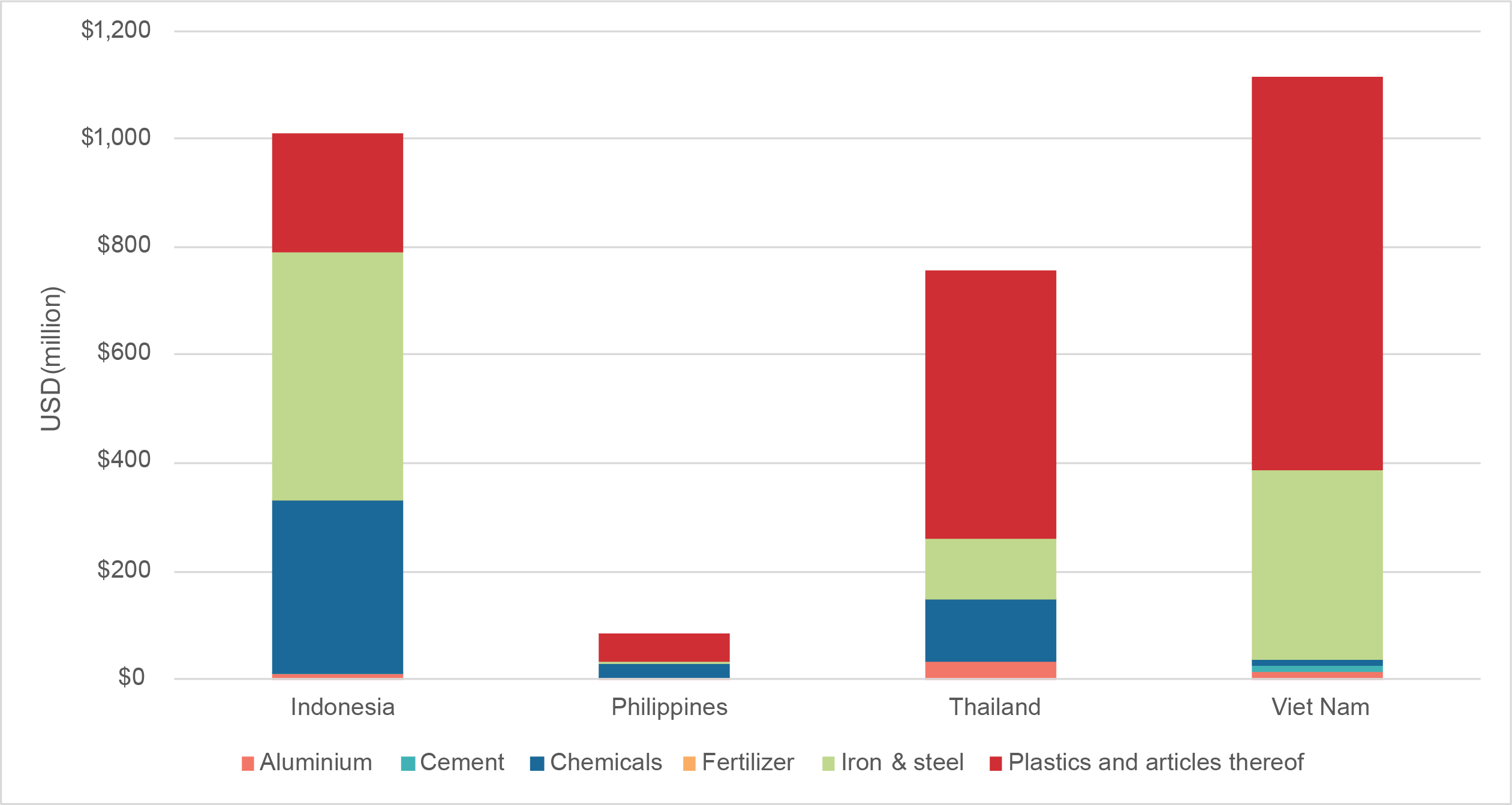

The introduction of CBAM by the EU is likely to affect Viet Nam, Indonesia and Thailand the most amongst Southeast Asian countries. Exports of plastics, iron and steel, as well as certain chemicals, make up the largest shares of affected commodities. Between USD 0.7-1.1 billion of annual exports to the EU from each of these three countries may fall under the coverage of CBAM (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Export value of CBAM-relevant commodities to the EU, based on 2019 trade data.

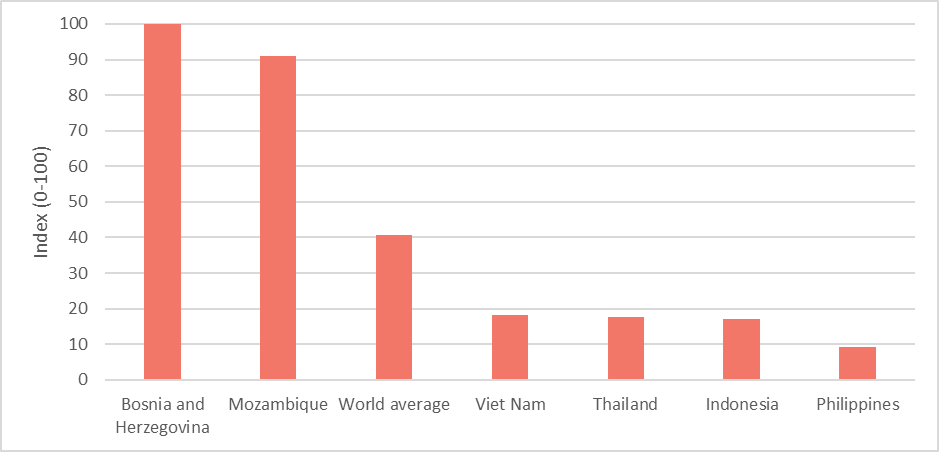

While the absolute exposure is notable, none of these countries’ overall GDP is highly dependent on CBAM-affected exports. Instead, these countries have relatively diversified export sectors that are not concentrated on the EU market. As a result, neither Viet Nam, nor Thailand, Indonesia, or the Philippines are highly vulnerable today to the introduction of the CBAM (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: CBAM normalized vulnerability index. The normalised vulnerability index represents uniformly weighted index of export contribution to GDP (dependence), exports of CBAM-relevant commodities as a share of total exports (diversification), as well as exports to EU as a share of total exports (concentration). Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as Mozambique, are shown for comparison as they represent the most vulnerable countries.

Whilst none of the four countries we analysed seem highly vulnerable to CBAM at the aggregated economy-wide level, we use our CLIMTRADE model to show that producers and exporters of affected commodities in Viet Nam, Thailand, and Indonesia should still expect the CBAM to have notable economic impact for their businesses.

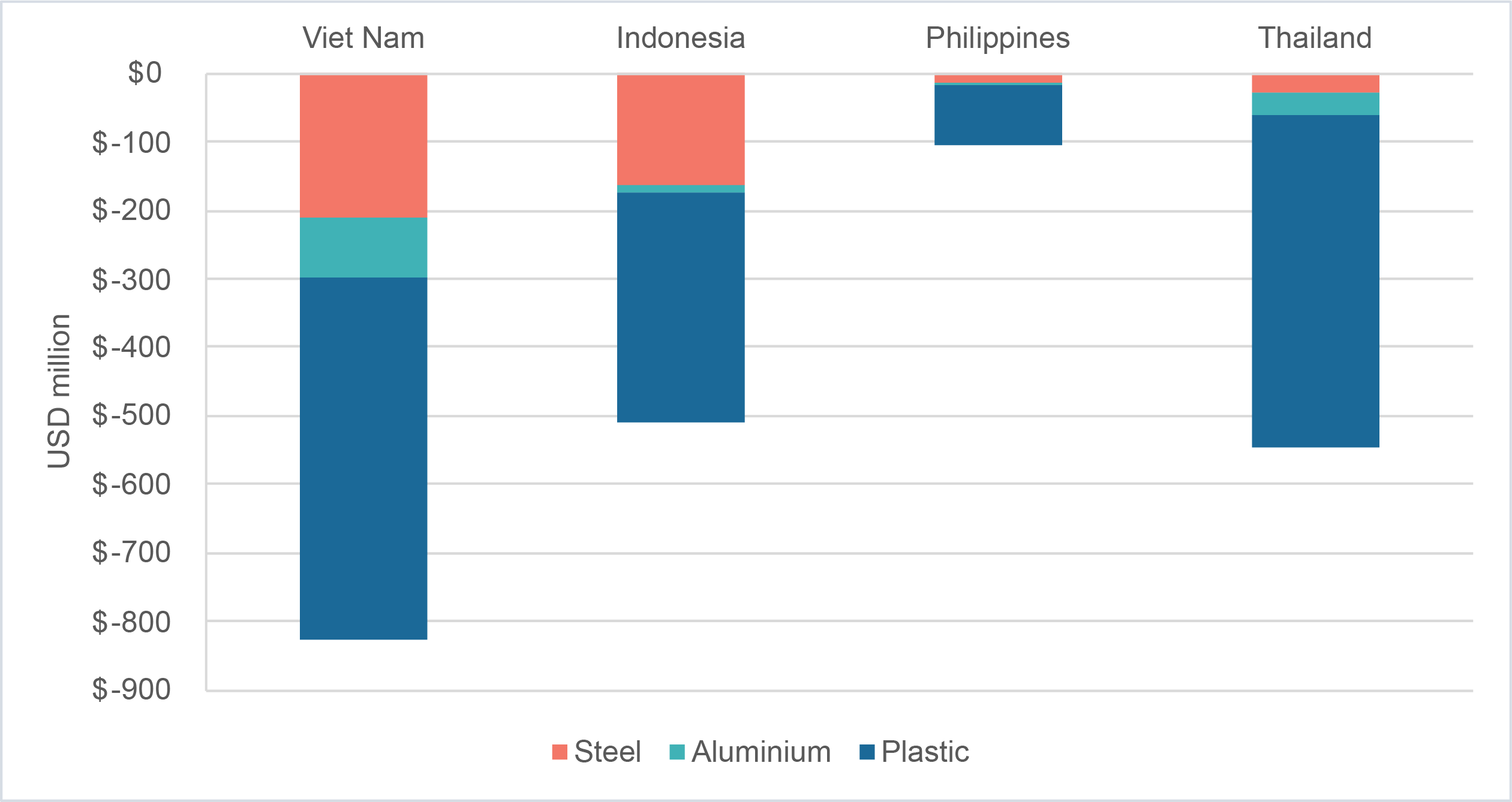

Over the past six months, EU allowance market prices have risen from approximately USD 70 per tCO2 to over USD 100 per tCO2. Under a carbon price of USD 90 per tCO2, we find that specifically exporters of plastics would likely incur large losses, i.e. forgone revenue that they would have been able to generate in the absence of CBAM (see Figure 3).

In Viet Nam, we estimate CBAM could lead to annual forgone revenue of around USD 830 million for exporters of steel, aluminium and plastics covered by the mechanism. This equates to cutting approximately 0.6% off its annual GDP. We also estimate, using the CLIMTRADE model, the potential implications of reduced demand for exports on domestic employment and find that CBAM could lead to almost 10,000 lost jobs in Viet Nam alone.

The impacts in Thailand and Indonesia are less pronounced, but still significant. Both countries may potentially face revenue losses of around USD 500 million per year. For Thailand this translates into reductions in GDP of 0.2% and job losses in the order of 5,500 per year. For Indonesia, CBAM could imply a 0.1% cut in annual GDP and almost 8,000 fewer domestic jobs. Impacts on the Philippines are marginal in comparison. Plastics, the main driver of these impacts, are currently not included in the commodities covered under the initial design of the CBAM, but the EU Parliament is pushing for its inclusion.

Figure 3: Export revenue as the result of an EU CBAM at a carbon price of USD 90 per tCO2. This analysis only covers exports of steel, aluminium, and plastics.

Impacts and risks could inflate in the future

Unilateral enforcement mechanisms such as the CBAM may trigger responses from other key markets, ranging from protest and retaliation in the worst case, to better cooperation and aligned action on carbon pricing between countries in the best case, e.g. in the form of so-called climate clubs. As international markets become increasingly carbon-constrained, a larger share of Southeast Asian countries’ exports will become affected, and the resulting value at risk for export-oriented industries will grow larger.

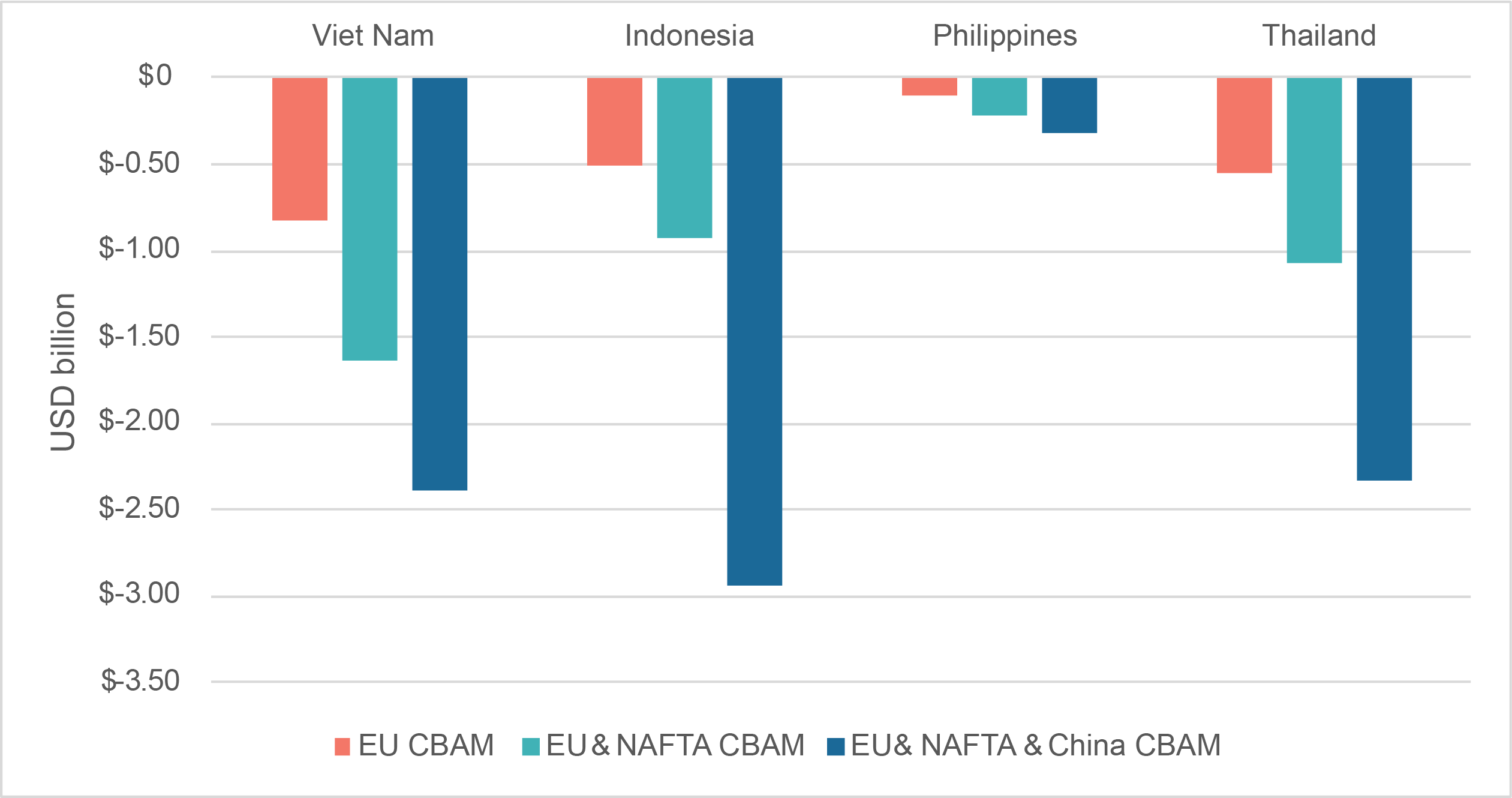

For example, if the United States, Canada and Mexico (under the umbrella of the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA) were to join forces with the EU in forming a climate club and introduced a coordinated carbon border adjustment mechanism along the lines of CBAM, this may almost double the revenue at risk in Southeast Asian countries as a much larger share of their exports would be affected (see Figure 4). Naturally, economic impacts are even greater in a hypothetical scenario in which China joins the club. However, the formation of these climate clubs and coordinated border adjustments requires that these countries and jurisdictions introduce nation-wide carbon pricing mechanisms compatible with that of the EU, which is unlikely to happen in the very near future.

Figure 4: Export revenue (steel, aluminium, and plastics) as the result of coordinated CBAMs at a carbon price of USD 90 per tCO2.

Opportunity for competitive advantage

The decarbonisation of international trade flows will have a lasting impact on trade patterns. The competitiveness of goods produced by exporting countries is no longer just a function of traditional factors of production such as land, labour and capital. The cost of carbon associated with the production of goods already represents a decisive cost factor in regions and sectors that fall under a carbon pricing regime. With carbon border adjustment mechanisms such as the EU CBAM, also producers and exporters in third countries are facing these economics.

As importing countries increasingly price-in the cost of carbon to protect domestic industries and to ensure the effectiveness of local climate policies, producers and exporters must minimize their carbon footprint and the associated costs to remain competitive. This represents an important opportunity: Those producers and exporters that are fastest to adopt are likely to see significant returns on their investment to decarbonize, as their exports become comparably more competitive in carbon-constrained markets.

Decarbonising heavy industry sectors takes time, is costly, and requires significant investments in research and development. It is unlikely that producers and exporters, specifically in credit-constrained developing and emerging countries, are realistically able to stem the required investments to rapidly advance their export sectors’ decarbonisation. Exporting countries and especially those vulnerable to mechanisms such as CBAM should make use of the CBAM pilot phase to find ways through which they can support domestic producers and exporters to be prepared and take opportunity of future carbon-constrained trade regimes. At the same time, vulnerable developing and emerging countries should move ahead with their own carbon pricing instrument, which ideally can be credited against the CBAM, to support the decarbonisation of their economies domestically.

|

The CLIMTRADE tool CLIMTRADE was developed by NewClimate Institute to support the quantitative evaluation of economic impacts associated with the introduction of carbon border adjustment mechanisms. Understanding countries’ exposure to trade-related transition risks is essential for defining informed policy responses. As part of NewClimate’s COMPASS toolbox of open-source models, CLIMTRADE draws on the global simulation model by Francois & Hall (2009), a multi-country global market partial equilibrium representation of industry- or product-level trade flows. CLIMTRADE explicitly models carbon border adjustment mechanisms as a function of a commodity’s emissions intensity and an underlying carbon price. Further, the tool allows users to run mitigation scenario analysis to explore the economic impacts of cutting emissions for certain goods. CLIMTRADE translates trade shocks into domestic economic impacts through Input-Output analysis, reflecting national data that captures the relationships and interdependencies between different sectors. Calculations in this blog use publicly available data only. Trade flow and tariff data are drawn from UN COMTRADE and UNCTAD TRAINS for the year 2019. We draw on data for domestic production and carbon intensities of products from industry reports and the scientific literature. For iron and steel, regional production volumes are based on EUROFER and carbon intensities are based on ERCST. In the case of aluminium, we used production data from the International Aluminium Institute and carbon intensity factors from ERCST. For plastics, we used production data from PlasticsEurope and emission intensity data from the Coalition on Materials Emissions Transparency. |

About CASE

The programme “Clean, Affordable and Secure Energy for Southeast Asia” (CASE) is jointly implemented by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH and international and local expert organisations in the area of sustainable energy transformation and climate change: Agora Energiewende and NewClimate Institute (regional level), the Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR) in Indonesia, the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities (ICSC) in the Philippines, the Energy Research Institute (ERI) and Thailand Development Research Institute (TDRI) in Thailand, and Vietnam Initiative for Energy Transition (VIET) in Vietnam.

Funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK), CASE aims to support a narrative change in the region’s power sector towards an evidence-based energy transition, in the pursuit of the Paris Agreement goals.

About GIZ

The Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH is owned by the German government and has operations around the globe. GIZ provides services in the field of international cooperation for sustainable development. GIZ also works on behalf of other public and private sector clients both in Germany and overseas. These include the governments of other countries, the European Commission, the United Nations, and other donor organisations. GIZ operates in more than 120 countries and employs approximately 22,000 staff worldwide.